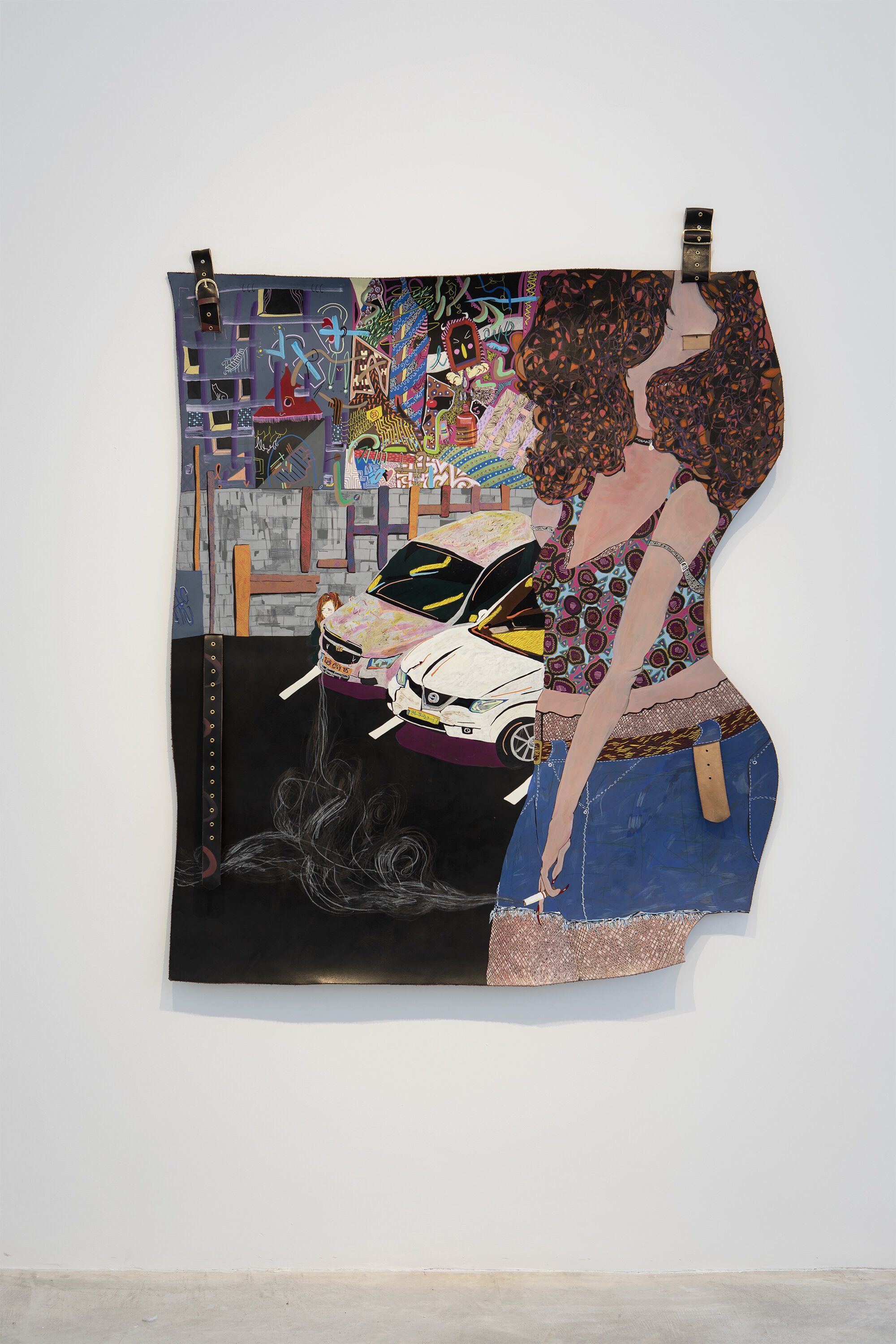

Parking Lot Whispers | Shir Moran

May 16th - July 5th, 2019

© Shir Moran

The view from the window of Shir Moran’s house in south Tel Aviv is of a neglected parking lot. After dark, the area pulsates with life; hookers, johns and drug addicts leave traces that are visible the morning after. The painting, and the title of this exhibition, originated in an image that became etched in the artist’s memory. In the early morning hours, a pretty, young woman, probably a drug addict, crouches in the parking lot behind a row of cars, hiding from some unseen threat.

The whispers and nocturnal sounds coming from the parking lot, the stirring of passions and minor offenses, traces of exploitation, the grey area that stretches between the ethical and the sleazy, accompany the works like a backdrop of a sideshow. The imaginary voice of the talking cricket; the voice of the conscience in the children’s story Pinocchio, resonates in the face of that scenery. In Carlo Collodi’s book, the cricket serves as the Apollonian voice cautioning Pinocchio to behave morally and not give in to his Dionysian desires. Though Pinocchio kills the cricket early in the story, its voice accompanies the wooden boy during his ordeals and adventures.

The artist’s second work for the show, titled Boy, depicts the naked Pinocchio running from the police. In the story, Pinocchio runs away the moment Geppetto finishes carving him. He doesn’t yet know who he is, nevertheless, his first instinct is to escape. This is also why he isn’t wearing any clothes. A tree in nature is not naked, but the moment the creator’s hand touches the block of wood, he is. His first “impulse” is guilt and shame, like Adam and Eve.

“Ready Pinocchio! Before starting your performance, salute your audience!”

So says the evil circus manager who bought Pinocchio after he had turned into a donkey.

Poor Pinocchio had been tempted by a “pied piper” to go to the Land of Toys—a place that was like an early version of pop star Michael Jackson’s “Neverland,” a dreamscape that embodies the tension between the desire to be looked at and simply to be. Pinocchio is also torn between two desires: to be a real boy instead of a wooden marionette and to be a good boy and resist worldly temptation and evil inclination. The tensions are a pair: just as a real boy is subject to his whims and urges, a doll is always good, satisfying and pleasing to its owner.

The representations in the paintings of Shir Moran are engaged in an internal conflict, torn between the desire to be an object, to please, to be the object of passion, and to be an enlightened, progressive subject, aware, decisive, conscientious and rightful. They enact complex relationships with objects; they are not subjects appropriating or consuming other objects, rather, they yearn to become objects themselves. Featured in the works are characters from the movie Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Pinocchio, the shadow of the talking cricket, the Fox and the Cat and even the famous Playboy model Anna Nichole Smith.

“If all the cats were like you, how lucky the mice would be!”

Shir Moran’s paintings can be viewed in feminine, laboring terms; indeed, the laborious paintings fulfil promises that hint at the decorative and ornamental. They are satisfying, exuberant paintings bursting with color and boasting a polished technique. Like the well-worn pickup line, the painting titled You Remind Me of My Sister, seems familiar, inviting and non-threatening. Lingering over it, however, it reveals itself to be duplicitous and disingenuous, betraying every naïve, childhood promise it ostensibly offers. Similarly, the feminine act that emerges from the painted surface presents a complex, even terrifying femininity.

The desire to realize the wish embodied in the male gaze is found both in the work’s painterly expression and in its very content. The women in them are torn between a desire to attract and to be objectified by the viewer’s gaze and rejection and revulsion conveyed through their own empty gazes. Traces of mysterious, possibly even malicious acts appear in the dubious setting. An intense sense of uncanniness emerges from some of the “Twin-Peaks”-like scenes. In these scenes, women in various poses and situations replicate the place of the conflicted cartoon—the desire to exist as object and human being. They partake in complex relationships with their medium. It is what defines their being. In this sense, Moran presents femininity, childishness and animation as mediums, formats that require its subjects to consolidate into or conform to the medium’s boundaries.

The sense of dread is heightened by the realization that Moran paints on leather. One can see the outline of the body of the animal whose skin serves as the painting’s support. Most animals that have been mistreated carry the marks of their abuse on their carcass. The submission of the animal, woman or child reverberates in the encounter with the animal skin. Painting on a dead animal.

The duality evoked by the paintings’ supports, engulfs their place as objects, mega commodities, desirable paintings on commercial display, which cannot be separated from their origins as animals, suffering soul or object to be appropriated. The belts which pierce them, chain the painted skins to the wall, declaring them branded, desirable goods.

“I am not a fish at all, I am a Marionette.”

“Well if you are not a fish, why did you let this shark swallow you?”

“I didn’t let him. He chased me and swallowed me without even a ‘by your leave’! And now what are we to do here in the dark?”

“Wait until the shark has digested us both, I suppose.”

“But I don’t want to be digested!” shouted Pinocchio, starting to sob.

“Neither do I,” said the Tunny, “But I am wise enough to think that if one is born a fish, it is more dignified to die under the water than in the frying pan.”

“What nonsense,” cried Pinnocchio.

“Mine is an opinion,” replied the Tunnya, “and opinions should be respected.”

Moran uses varying degrees of compression and intensity to etch, score, draw and smear the leather. The artistic acts—the dragging of paint brushes and scrub brushes and tools for piercing, across the “canvas”—harness dimensions of violence and exploitation. A belt that replaces a missing hand, or that emerges from a figure’s behind completes the flow of the internal painterly act into gazing at the picture as an object. The action leaks out.

In many of the works, Moran has divided the leather by first cutting and then working almost intuitively and often repetitively on the various parts. Thus, the encounters between the different parts of the painting appear like fluid or circular transitions between aggregate states. Each work has a total independent movement and each section a separate internal one. But the distinctiveness of the parts is clearly fluid, osmotic, non-hermetic. And it glides down the wall, into all the objects in the “exhibition” format.

Moran does not create perspective in a technical way. Rather, it emerges from the relationships of the surfaces. The rich patterns spread over the leather create foreground and background, but within this they do not build an illusion of light and shadow. Their flatness conjures the image’s movement and depth. Thus, even a flat image, in its broad sense (looking at a woman as an object, the dissolution of a child to the point of its being merely a means, viewing an animal as a tool), both embodies and presents a complex and layered picture. In other words, flattening as a painterly strategy is what points to the image’s depth, problematic nature and complexity.

All the paintings in the exhibition have humorous or enigmatic titles that beg to be deciphered. Moran “concludes” the process by placing the viewer in the same ambiguous moral field. On the one hand, the collector or critic who appropriates the flat image for their own pleasure. On the other, the thinking reader who is asked to study the work in light of its particular, charged, multivalent title.